Students participate in cybersecurity and biothreat defense internships

CBTS held its inaugural Summer Research Institute in Year 5. These programs were envisioned to provide onsite laboratory experience for promising undergraduate students in STEM field with Texas A&M University System faculty mentors conducting DHS mission-relevant research. Additional program elements included interactions with DHS stakeholders, professional development seminars, and field trips to DHS Ports of Entry. Two topics were chosen for this first year, biothreat defense and cybersecurity due to faculty mentor strengths and pre-existing relationships with DHS customer stakeholders at CBP, USCG, and DHS S&T.

Cybersecurity

The U.S. faces ongoing and increasingly sophisticated malicious cyber campaigns that threaten the public and private sectors and, ultimately the Nation’s privacy and security. To help address these challenges, the Cross-Border Threat Screening and Supply Chain Defense (CBTS) Center of Excellence (COE) partnered with the Texas A&M University System RELLIS Academic Alliance and Texas A&M University-Commerce (A&M-Commerce) to establish a “Summer Research Institute” in the discipline of cybersecurity. This annual program will help build a future homeland security science and engineering workforce by engaging undergraduate students on research projects encompassing prevention, detection, assessment, and remediation of cyber incidents. In its inaugural year, the CBTS Summer Research Institute supported faculty who are subject matter experts in cybersecurity, and upper-class undergraduate student teams, in hands-on 10-week summer research programs with the goal of fostering more secure cyberspace. Invited guest lectures and field trips with industry and DHS officials rounded-out student experiences with opportunities to learn about different career opportunities.

Of the eight selected students, four were onsite at A&M-Commerce in Commerce, and four were at the RELLIS campus. The students worked in teams of four, with two students from one location working with students at the other location. This team approach was used to reflect a “real-world” work environment where teams may be physically distributed. In addition, the students had the opportunity to participate in each of the two projects, one on Next Generation 911 and one on Maritime cybersecurity.

Vessels’ Engine Control Rooms

In collaboration with DHS, the students were able to take a close look at the ships at the U.S. Coast Guard Sector Houston-Galveston. The students were able to tour a Tony Tug vessel and a Ferry Vessel to examine the levels of automation, operational technology, and communications systems. Technical staff discussed cybersecurity threats, common operational technology (OT) and industrial control systems (ICS) (OT/ICS) security challenges, and USCG standards.

This was the first time that all the members of the group were able to take a close look at the vessels with a focus on maritime operations, systems, cyber-attacks, and security. Within the vessels, the engine control room served as a hub of essential equipment, camera system, and navigation systems for internal ship activities including monitoring and alerts, driving, navigation as well as various communication channels for redundancy.

The students discussed and summarized potential attacks on the vessels’ vulnerabilities including the bridge, internal control room, and potentially the engine control room. The majority of the ship’s technological equipment (engines, for example) are analog and rely on electric signals received from control sections. Every ship system has multiple layers of redundancy to mitigate the risk caused by any single attacker. Camera systems are used to monitor the ship at all times, besides physical patrol and monitoring. The majority of systems still heavily rely on passwords for access, which may be susceptible. Failures in manual-shipping systems and monitoring systems could combine to cause major issues.

The group discussed with USCG technical staff and cyber security experts about existing cyber security threats and attacks, like GPS spoofing. Nonetheless, implementing changes, system updates, and automation integration are challenging due to constraints caused by current policies and regulations as well as a scarcity of professionals and high demand. Security compliance is still lacking. There are gaps among the actual Maritime systems, policies and regulations, and current international and domestic requirements. To actively contribute towards bridging those gaps, in the Summer Research Institute, students and faculty mentors worked collaboratively on the research project “Towards Zero-Trust: A Systems Engineering Approach for Vital Ship Systems’ Cybersecurity Risk Assessments.”

During daily research team progress meetings, the students presented their findings, talked about problems, and received advice. Mentors provided constructive feedback on research approaches, data analysis methods, and the main direction of the projects. These meetings helped keep the students on task and focused on their study objectives. In the weekly group meetings, the students and mentors reported on the research projects in general, summarized lessons, and collaboratively charted a plan for the forthcoming week. To promote collaboration and foster a conducive environment, students engaged in peer reviews and small group cooperation. Each student had a partner from the other campus in the research project and actively communicated to help one another. This dynamic helped students break communication and technical barriers, encouraging them to embrace diverse perspectives and enhance the clarity and efficacy of their work.

At the completion of the internship, each student presented their findings and solutions to the research questions identified in the Summer Research Institute. This was the first time any of these students worked collaboratively within a research team, focusing on real-world cybersecurity research questions. Another positive outcome is that one of the students will be able to continue their senior thesis working on this project.

Biothreat defense

Biological threats and hazards can significantly impact the Nation’s health, critical infrastructure, and economy. To help address these threats, the Cross-Border Threat Screening and Supply Chain Defense (CBTS) Center of Excellence (COE) partnered with faculty from AgriLife Research in College Station and near the U.S.-Mexico border at Weslaco to establish a “Summer Research Institute” in agriculture biothreat defense. Field trips included reciprocal visits to view research facilities on each campus, and a trip to the Pharr International port of entry for discussions with Customs and Border Protection on border safety, cargo inspections and pest identification, non-intrusive inspection methods, and enforcement related to agricultural pests and diseases. The hands-on 10-week summer research projects for the six fellows encompassed biological threats to livestock and produce including tickborne cattle tick fever, locust swarms, tobacco mosaic virus, and citrus greening.

SRI team meeting with CBP Ag Specialists regarding fresh produce inspections, with CBP and K9 Officers regarding enforcement, and the entire group with DHS CBP .

At the Pharr International port of entry, the student fellows met with the Port Director and Assistant Port Director, Supervisory Program Manager for Agriculture, and CBP Agriculture Specialist, who discussed border safety, cargo inspections and pest identification, non-intrusive inspection methods, and enforcement. The team toured various inspection areas, systems, and facilities used to protect the U.S. against agricultural pests and diseases. Students also met a CBP officer, Dr. Sonia del Rio, who shared her career path as an undergraduate and graduate student at TAMU, to a research scientist at Texas A&M AgriLife, and ultimately to pursue a career as a CBP Agriculture Specialist. Additional presentations were given by Dr. Romel Lapitan and Mr. Jared Franklin, who each discussed their career path and duties of their respective offices within DHS. The students were very interested in learning about alternative career pathways and the education and training involved.

Plant experiments in artificial grow lights and plant incubators at AgriLife Weslaco.

Plant experiments in artificial grow lights and plant incubators at AgriLife Weslaco.

Biothreat Defense student fellows and faculty mentors at the AgriLife Research and Extension facility in Weslaco, Texas.

By the end of the program, students were evaluated based on their knowledge during presentations and submitted mini-theses. They met all the expected performance measures. For instance, the students in Weslaco were able to learn the various research methods useful for plant disease identification using visual symptomatology and molecular (e.g., PCR) technologies. Students also learned to identify pests and insect vectors that transmit diseases (e.g., citrus greening, TMV). Similarly, students in College Station learned about how to use Raman spectroscopy (RS) to accurately (above 90%) determine plant stresses as well as identify tick species (Ixodidae) using cattle feces. Students collected and analyzed Raman spectra from various samples and learned to differentiate among tick species. Students that worked in Kurouski lab also learned how to express and purify proteins. Importantly, all students learned how to conduct scientific research and collect scientific experimental results, analyze and interpret research data, and report it in a concise scientific report. All these research experiences helped students further their knowledge of emerging zoonotic and agricultural threats and how to tackle these threats through enhanced detection, identification, and exclusionary efforts of high-risk products and materials at U.S. ports of entry. Lastly, but importantly, the exposure to multiple professional development seminars by various speakers helped broaden their future career opportunities in DHS and USDA.

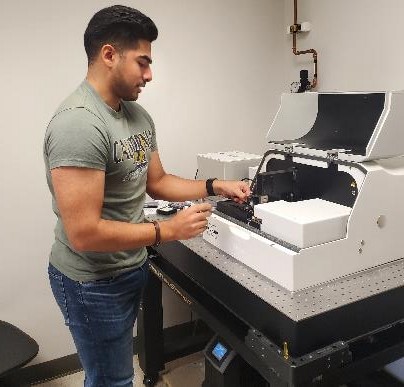

Research at Texas A&M AgriLife in College Station